“Am I Enough?”: The Struggle Of Being A First-Generation Child In America

In recent years, the growing population of first-generation children being born in the United States has risen tremendously.

A first-generation child is when two foreign-born parents immigrate to the United States and form a new family. This term is usually a sensitive topic for many because of the struggles some have faced being a first-generation in the United States.

Yet the identity of being a first-generation child is rather unique than a burden. The uncommon struggles that one experiences isn’t something everyone faces. Therefore, first-generation children become the toughest people due to all the lessons they’ve learned in the U.S.

The U.S is a melting pot of different cultures and traditions, so many find it difficult to adapt to their own culture. There can be a struggle of attempting to fit into the U.S. while also retaining said individual’s culture, all while their first language may not even be English.

Therefore, learning and speaking English for many years, first-generation children tend to “lose” their native languages, causing insecurity within them. With their vocabulary slowly reducing, many tend to feel a cultural crisis and a lingering question of, ”Am I enough?”

The question stems from children who begin to lose touch with their culture, traditions, and language. While many are born and raised in the U.S, they are torn between fitting in American society and their heritage.

While faced with this debacle, others like Da Vinci Communication’s Vice Principal, Andrew Daramola, have finally come to terms with their identity.

While this pressure continues to linger, the decision of continuing to proudly state your heritage comes into play. As many disregard their heritage, the ones who don’t are advocates for their culture and origins of their roots.

“I would say just learn about your different cultures, and that you don’t have to like your Hispanic culture. You don’t have to like it. Just know who you are,” said DVC Sophomore Daniela Torres.

Who expresses the importance of heritage in your identity, regardless of feeling “not enough,” your roots are what created your appearance and your uniqueness in any society.

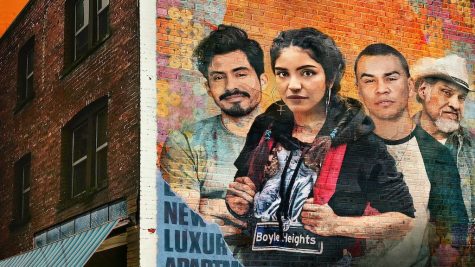

Additionally, many first-generation children continue to feel unseen by media representations and lack of school lessons. For example, due to media portrayals, people can interpret all Hispanics/Latinx as Mexicans, without considering other countries, accents, and use of slang.

“They don’t realize that there are also a lot of other countries that speak Spanish. Just like Venezuela, Colombia, Cuba and etc. It’s just like, you know you just have to appreciate the other countries instead of just one,” said proud Mexican-Velenzulan Sophomore, Laura De Luna.

The lack of teaching on world countries and their cultures plus traditions, causes many to make prejudiced assumptions and racial categorization.

Now, being a first-generation does not necessarily mean that they want to remove their American identity. Instead, it’s a middle ground conflict on trying to fit in with others without feeling excluded simply because of others’ expectations.

While trying to balance life as two separate identities, can cause multiple anxieties within first-generation children. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, “A person born in the U.S. to immigrant parents may experience conflict between the attitudes, beliefs, and values of the parents’ culture and those that are more prevalent in the U.S. Parents will often try to preserve their cultural roots through maintaining beliefs and practices from their home country, while their U.S.-born children may separate or dissociate from their parents’ beliefs due to a lack of strong connection to the country of origin or a desire to be ‘more American’.”

Just like the wise words from Daniela Torres, “you don’t have to like your heritage, just know who you are,” demonstrates that regardless of societal pressures, the heritage that runs within oneself cannot be ignored for posterity.

Bridget Reyes is currently a junior at Da Vinci Communications High School. She is apart of the Vitruvian Post as a staff writer and a member of our broadcast...

Kimberly Perez is a junior staff reporter at The Vitruvian Post. Her beat and some of her articles include international news, human rights, and foreign...

Fariha Ahmed • Oct 1, 2021 at 8:57 am

This article was amazingly written in portraying the hardships and identity crisis first-generation individuals feel in this country. It explained how your background can influence your role in America since you don’t feel as connected to it or feel like you don’t fit in society standards. I could also heavily relate to this feature since I am too a first generation born in this country with two immigrant parents, and everything written/said was true to me as well. Growing up with parents with broken english and unique culture, I definitely had struggles with my identity and expressing myself. At times I would also feel ashamed for it due to what others around me thought. Lastly, the quotes from the interviews had meaningful messages and really made on the feature article as well. Clear and significant points were stated in this article and it was really easy to follow and understand.